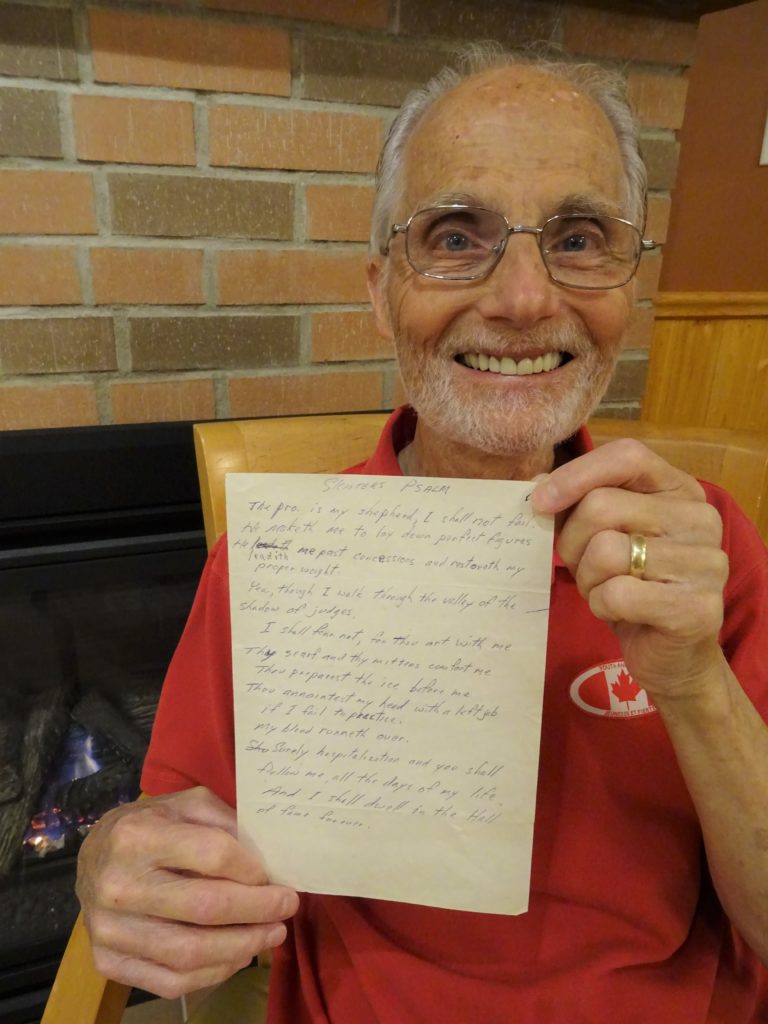

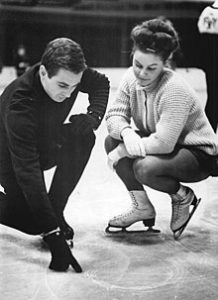

Featuring Manon Perron

In these days of multitasking, there is no better expert than today’s guest on the Alumni Podcast, Manon Perron. Manon has mastered it all, from being a skater, local/national and Olympic coach, team leader, mentor, and now as a Skate Canada Advisor to the High Performance Program. Her energy and passion for the sport and for developing skaters’ skills beyond the ice, and her contributions to high performance are immeasurable. Manon and Alumni Chair Debbi Wilkes caught up recently to talk about Manon’s incredible career and her continuing dedication to skating in Canada.

![]()

Life After Gold

by Kaetlyn Osmond, Three-time Olympic medalist

Winning a world championship was something I never imagined. I never believed I had the ability to accomplish something that prestigious. I never put my name beside the likes of Barbara Ann Scott, Petra Burka, or Karen Magnussen – they were the gold medal women of Canada, I wasn’t one of them. Until one day, I was.

The night I won, I felt so light. I felt like I was floating up over the world and no one could pull me down. I was awake, I was alive, I felt beautiful. I could relax, I could breathe, I could smile without force. That high lasted about three days, and then I collapsed.

Following the world championships in Milan, Italy, I headed straight to Japan for “Stars on Ice”. I got there a day before rehearsals to catch up on sleep. I slept for eighteen hours straight, waking up long enough to eat some extremely unhealthy room service, and then going back to sleep for another ten hours. Nothing I could do would wake me up. It was wonderful.

The world got busy again. With the rest of the cast arriving in Japan, we all headed to the rink for a week of long hours of rehearsals for the show. It was great seeing and chatting with everyone and getting to the work I love…PERFORMING. What I noticed that week was how quickly winning a world championship can be forgotten. I wanted to celebrate and embrace the fact I did something worth celebrating, but no one seemed to be on the same page as me. Throughout the rehearsal week, I felt my championship drift further and further away, dragging a large part of me with it. My high was left in Milan, only exhaustion remained.

Then something magical woke me from my slumber.

“World Champion, Kaetlyn Osmond.”

I was behind the curtain, about to step out on the ice when I heard those words boom through the speakers for the first time. Those words, that belief, that reality, lifted me up and guided me forward. Every single time I heard those words, it seemed otherworldly. I was a part of a new dimension. The world was dark, except for the spotlight illuminating a circle onto the ice. It was just me and the ice. It was just my breathing. It was just my own body working. It was my world where there was no hiding. Those words got me through months of shows and celebrations.

Finally, the shows for the season were done and so was I. I couldn’t stay up in the clouds anymore. I needed rest. I needed quiet. I went on vacation, leaving all my technology behind. I laid down on a couch for a week, never turning on my phone. I started spending some time with friends on my third week off, and then it was time for me to get back on the ice. I didn’t want to as I still didn’t have the physical and mental rest I needed, but I got on the ice anyway.

Strangely the ice no longer felt like home, it felt like foreign territory over which I had no control.

Talk of my world championship slowed to a nonexistent topic. The next season was already the main focus. I wasn’t ready for that. I wanted to live in my post World’s high longer, but the world didn’t work that way. I forgot how to skate. I was falling on doubles and not understanding why. What I did understand was I needed to take the Grand Prix season off. That decision led to the decision to take part in the “Thank You Canada Tour”.

That tour was something remarkably special. No words can explain the love amongst the cast and the connection to everyone in the building. But I lost who I was.

The performing that I lived for wasn’t giving me anything anymore. I was determined to find it though. I took the rest of the competitive season off and agreed to more shows. I skated in “Art on Ice”, club shows across Canada, a tour in Korea, and “Stars on Ice” in Canada. Every show day made it harder to make it to the next show day. I started having anxiety attacks before getting on the ice and as a result, lost any remaining belief in myself.

During all these shows and dealing with an overwhelming amount of emotions, home stopped feeling like home. Edmonton was where I trained to accomplish all these unbelievable dreams, but the memories of that were too painful for me to stay. So, I left. I left my home for Ontario, in search of a new home. I contemplated never skating again. I contemplated never stepping foot on the ice for any reason. I felt guilty to be called World Champion. I felt undeserving of that title. I didn’t want to be connected to anything that brought me there. That title and those words went from being something that gave me life to being something that broke me down and made me want to disappear.

Friends convinced me to get on the ice to coach. Something I didn’t necessarily want to do, but it got me out of the house. Seeing kids motivated to train and willing to listen to me, made me slowly appreciate the magic of skating again. When it came time to agree to the “Rock the Rink” tour, I hesitated. Scared of myself and scared of trying again. But with the help of friends and the skaters I was coaching, I agreed. They helped me get training again. They helped me take it step by step, the same way I was teaching them. I took comfort with my long-time choreographer Lance Vipond to choreograph a program that explained my emotions and aimed to inspire the girls I was connecting with. I was scared, but I got to the rink every day.

The “Rock the Rink” tour was my last round of shows. At the beginning of the tour, I was embarrassed of myself every time I stepped on the ice. Towards the end of the tour, I began feeling inspired and my views on my skating changed. I stopped living in the life of a World Champion. It meant nothing in the real world. Being compared to who I was when I won, was breaking me. So, for the second time in a year, I changed my life completely.

I moved to Toronto. I moved into an apartment on my own. The first time I was ever truly alone. It wasn’t easy, it still isn’t easy, but I needed to distance myself from anything and anyone that was connected to the days that I could win.

I was no longer winning, and I needed to learn how to deal with that reality. I needed new inspiration to make me win myself over again. I connected with new people. I reconnected with old friends, I applied to school, I started a new website, I tested new cafes and ate at new restaurants, and walked through new parks. I wanted everything I did to be new.

That included a new me on the ice. I worked with Jeremy Abbott, Kurt Browning, and Jessie Garon for the first time and told them I needed to be different. I didn’t want to be compared to who I was because that isn’t who I am anymore. I am not one to control my emotions or pretend everything is perfect, I am someone who is living in the world of the vulnerable and not afraid to show it.

I am looking forward to the person I can become. Using the knowledge of my past, with my excitement of the future to discover who I am now. It isn’t easy. Life before gold wasn’t easy, so why should I expect the aftermath to be.

Life after gold is a discovery, one without a direct path or the instant gratification of competition.

Life after gold is a self-learning process when you are no longer relevant in the topic of conversation and no longer trending on social media.

Life after gold is finding comfort in yourself when everything is changing around you. I am proud of what I accomplished on the ice and the people I connected with, but I am also proud of my search to find a completely different person since then.

![]()

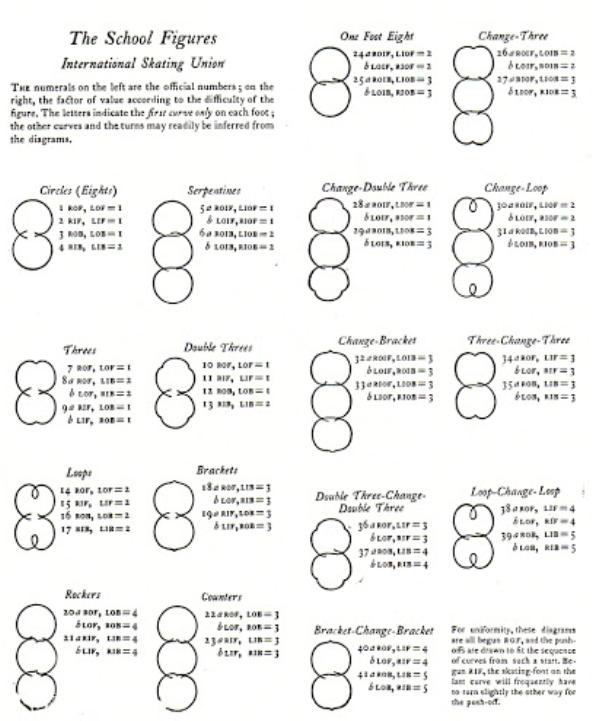

Like many of us during the COVID-19 lockdown, 1962 World Champion Don Jackson spent some of his time sorting through long-forgotten boxes, files, and folders. Amongst his vast memorabilia, he found The Skater’s Psalm. Although it was written in his own handwriting, Don cannot recall whether it was his own creation or the work of someone else. If it wasn’t Don’s and you can identify the name of the original author, please let us know.

In the meantime, enjoy The Skater’s Psalm.

Skater’s Psalm

“The Pro is my shepherd, I shall not fail.

He maketh me to lay down perfect figures

He leadeth me past concessions and restoreth my proper weight.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of judges,

I shall fear not, for thou art with me

Thy scarf and thy mittens comfort me.

Thou preparest the ice before me

Thou annointest my head with a left jab

if I fail to practice.

My blood runneth over.

Surely hospitalization and you shall follow me

all the days of my life

And I shall dwell in the Hall of Fame forever.”

![]()

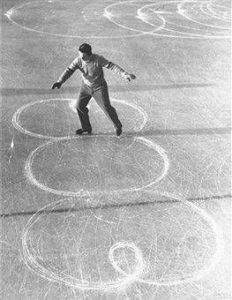

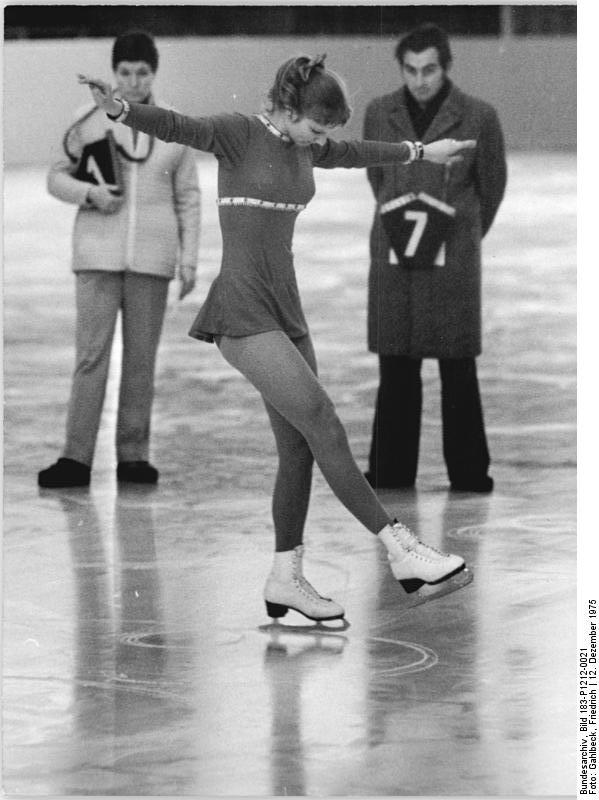

It Figures!

by Nancy Sorensen, retired official

I never really liked school figures. They were so regimented and precise, offering no place for imagination or creativity. I much preferred to jump and spin to music.

Figure practices, called “patch”, for your patch of ice, were quiet places, in empty arenas, save for skaters and coaches.

Patch was an hour and if you were lucky, there was nobody across the ice from you giving you a “double patch”, ideal for three lobe figures. If you were not so fortunate, you and the other skater dodged each other while encroaching on the other’s territory, to accommodate that third circle. When finished working a particular figure, you stepped one pace down from that centre, to start a new centre for a different school figure. During practice, you could see rows of centres slotted down each patch, with intercepting circles creating designs and patterns.

Skaters had their favourites, usually figures they did well. Despite my lack of enthusiasm, I had a knack for brackets. Some skaters could place turns with mathematical precision, others could grind out loops of near perfect proportions. Loops were practiced last because you could place them on top of your previous circles. Skaters knew patch was coming to an end when everyone started loops.

Although school figures were a quiet endeavour, there were definite sounds associated with them. Three turns “hiss”, brackets have a “tsk tsk” sound, rockers, and counters “swish”. Beware the silent turn! A strong, back push off has a short, soft grind. Does anyone recall the agony of those crucial push offs for the back one foot eight?

Every figure had its “rhythm”, enhanced by knee action and hip and shoulder positions. Loops particularly, had a special “movement” that indicated the skill of the skater to perform them correctly. For back inside loops, we were told to “stir the beans” with the free foot to assist getting that important, rolling action.

In today’s test system, the Skills still use these turns and loops in various exercises. At first, Skills were performed to music. The musical tempo was to help test candidates to maintain a pace for the exercises. However, the use of music was criticized for fear of having Skills judged like dance tests, which require strict adherence to the beat of the music. Hence, no music. Much to the amazement of coaches, some who have never skated figures, judges of older vintage, like me, can tell the quality of the turns and loops by their sounds and rhythms.

Initially, figure tests had three judges, single panel assessments were yet to come. All three had to pass every figure of your test! A candidate skated the entire roster even if destined to fail at its completion because of a faulty figure. Very time consuming! Later, rules allowed a skater to be “kicked off” a test if a figure was below par, a time saver. Then came the inauguration of the “reskate”.

Figure tests were serious business. My knees would either turn to jelly or concrete. The three judges observed your skating, then closed in, like vultures. One judge, quiet, solemn, in a grey overcoat, a hat and round glasses, scared me silly. As soon as I saw him, I felt I had already failed the test. I later met this judge, Sidney Soanes, when I began judging. He was pleasant, helpful, and greatly amused at my impression of him. It took joining the judges’ ranks to see that judges were just the same as everybody else.

On one occasion, my cousin and wife were visiting from New Zealand and insisted on accompanying me to a test session. “Bring a book; you’ll be bored,” I said. Instead, they watched with great interest. We, the judges, paced the layout, looking for consistent circles, checked edge line ups, determined placement of turns on the long axis, examined the centres, looking for flats, and zeroed in on the turns themselves. If we took a longer time to examine a figure, my visitors deduced, correctly, that something was wrong. They realized we were looking for symmetry of layout, a correct performance of a prescribed pattern. I have often wondered if an educated public might have found figures more interesting if they knew what judges were doing, aided, perhaps, by overhead cameras, like what is done with curling today.

There were eight figure tests in all. In earlier times, you could go from your seventh test straight to Junior Canadians and into Senior competition with successful passing of the eighth or Gold test.

Judging figures in competition was an endurance test. Hour after hour, you stood on the ice, walked, gingerly, through laid out circles, then held up your marks. Forget fashion. It was imperative to dress warmly and wear boots with good traction to stay upright on a slippery surface. There was one mark per figure, per skater, and three figures to be skated. Out came the judges, number boxes around their necks. Those boxes felt rather heavy after several hours. Your marking sheets, folded and crimped, had to fit on the back of the box because this is where you did your marking.

At some competitions, referees were equipped with sticks sporting flags, to indicate the turns, and mini brooms for sweeping them. To bring a bit of levity to a cold and serious setting, the occasional referee had a dollar in his/her pocket. The first judge to spill the numbers from the box while bending over to examine turns, won the dollar. Without brooms, and with the referees’ permission, we polished turns with our boots to better see them in perfect detail.

Competitors came when called, indicated the long axis with arms held shoulder high, then proceeded to skate. After examining the result, we, the judges, would stand side by side, like soldiers on inspection, and display our scores at the signal of the referee. Maneuvering the numbers in and out of the boxes with cold hands could be challenging!

Open marking was most daunting. You were forced to make quick decisions, no second guessing. Your most secret wish was that your marks coincided favourably with the rest of the judging panel! A large discrepancy, usually a full mark, such as 4.2 and 3.2, merited a mini on-ice conference with the referee, who requested explanations of the marks by the judges in question.

Skaters had their anxieties while awaiting the draw for starting foot (left or right), edge (inside/outside) and direction (forward/backward). Skaters practiced all prescribed figures prior to competition and hoped their favourite foot or edge would be drawn for their best personal results. Russian roulette in figure skating! In the 1940’s and 1950’s, figures counted for 60% of the total mark in competitive skating, dropping to a 50/50 ratio, then their final demise in 1990.

Certain skaters had reputations for excelling in school figures and Canada’s Barbara Ann Scott was one of them. Scott had the strongest, steadiest ankles which kept her on circles perfectly, in spite of turns, edge changes and shifts of body positions.

Internationally, I discovered European judges had a different way of looking at figures. Superimposition was everything. If you could lay out three consecutive tracings, one on top of the other, you must be good. North Americans focused more on how the figure was skated, with flow, and awareness for the symmetry and rhythm of the pattern. For any judge, from anywhere, standing for hours in chilly venues required stamina and an unflagging concentration. It tested one’s physical and mental mettle. Outside of the skating world, it is doubtful there was any inkling of the rigours involved with figures and their evaluation.

With the popularity of free skating and its potential for entertainment, figures were doomed. They were boring, tedious and time consuming. Their elimination brought predictions regarding figure skating’s future, both favourable and gloomy. David Dore, Director General of Skate Canada, remarked that with the end of figures, “Everybody will be skating in straight lines!”

Skating Skills and Transitions, two parts of the component marks in free skating, are strong indicators of competitors’ comprehension of those basic workings of the blade.

There are rumbles that school figures are making a comeback! Would the jumping jacks of today have the self-discipline and patience to carve out circles hour after hour? Would figures make a difference in the quality and intricacy of transitions? Can judges and coaches understand edges and turns if they have never done them themselves? What training would be required to educate prospective officials and coaches in the fine points of school figures? Questions abound.

I am glad I struggled through figures. It took my initiation as a judge to fully appreciate them and admire those who could perform them with precision and skill. Figure skating is called figure skating because of those circular patterns developed ages ago.

![]()

Five Questions with Barbara Underhill

Skating consultant discusses role with NHL players, Gender Equality Month

by Tracey Myers @Tramyers_NHL / NHL.com Staff Writer

March 31, 2020

NHL.com’s Q&A feature called “Five Questions With…” runs every Tuesday. We talk to key figures in the game and ask them questions to gain insight into their careers and the latest news.

The latest edition features Barbara Underhill, skating development consultant for the Toronto Maple Leafs and Tampa Bay Lightning.

Barbara Underhill was open to the idea immediately.

A former world and Canadian national champion in pairs figure skating, Underhill hadn’t thought about getting involved in hockey outside of taking her sons to the rink for their games. But in 2006, the coach of Guelph of the Ontario Hockey League (Underhill and her husband Rick Gaetz are part owners) asked if she would like to help improve Guelph players skating.

“I really missed skating, so I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll give it a try,'” said Underhill, who had been a skating commentator on television for 16 years before she was approached for this opportunity.

“I didn’t really know what I was getting into. I just remember getting on the ice in Guelph and just having this crazy feeling like I knew this was where I needed to be and where I needed to go. It just felt so good to be on the ice again. I had been on it my entire life. Being back on the ice was like, I felt I came alive again. So I made a decision at that point to leave broadcasting and take this up full time.”

Here are Five Questions with… Barbara Underhill.

How did those first sessions go and when did the NHL come calling?

“I jumped into it [in 2006] and started working with several of the players on the Guelph team. My focus was really just helping them and also trying to really figure out the science of it. It’s obviously very different on a figure skating blade than on a hockey blade. Playing a game is different than figure skating. There was a lot to figure out, and I sort of immersed myself, became obsessed with trying to figure it all out.

“Within about a year, I was getting calls from NHL teams. I guess they had seen players I was working with, seeing the results I was getting. I think my timing was really good, too. I got in at a time when skating was becoming more and more critical in hockey, it was becoming one of the most important things. But the funny thing was, (I) never said, ‘I want to be an NHL skating coach.’ I never said that. It just all evolved. When you love something, and you just do it out of passion, doors just start to open.”

How did you develop a program that worked for you?

“It was trial and error. One day I came home, my husband had been in a golf tournament and he had a video showing his swing compared with Tiger Woods. I could see what he was doing wrong. I’ll never forget that because it sparked something in me and I just said, ‘Oh, I could do this in hockey.’ This was before iPads and things like that, so I had to get this big video camera and I said, ‘I can do comparisons with players, but I’ve got to find my Tiger Woods.’ I knew at the time that [former NHL forward] Mike Gartner was known as one of the best skaters in hockey, he had won the [1996 NHL] All-Star skating contest. I called and asked him if we could videotape his skating, so that’s what I did. I studied how he moved, it was so efficient and effortless, so perfect, everything symmetrical. So I studied it and then I got some software that would allow me to upload players skating, film at exact same angle and put them side by side. I could show a player and say, ‘Look, here’s Gartner, here’s you. Look at how his knees are driving under his hips, yours are coming out.’ That was the biggest thing because, not only was I able to learn from it, the players were able to see it and most of them are so visual. When they can see it, they can do it and understand it better.

“My technique has evolved over 10 years, and I keep learning every day. I do things way different than back then, because I’m learning from players every day. I want to continue to learn and be better, find different ways, find better ways and think outside the box. Every player, for me, is like a puzzle. I just like figuring everything out, where the blocks are. When you move, everything needs to flow, every joint needs to move. If one is stuck, like your shoulder, it throws everything out of whack. So, we work on getting everything in synch, symmetrical and working like a machine. When I watch a player, I can see what’s out of synch and what needs to be done.”

What’s it like to see these players putting your lessons to work?

“It’s the best part about my job. when you see a player improve, when you see a player reach that next step, when you see a player play his first NHL game and texts you after and thanks you, I’m just one small piece of the puzzle. There are so many other people; there’s a whole village there trying to get to the next level. But it’s rewarding especially because I spent so much time with these guys 1-on-1. A lot of times I spend time with players coming back from injuries. I see players when they’re at a very vulnerable state. I really get to know the player and I think it’s the best feeling when you see a player reach that next level, knowing you played a small role. When I think of my career in figure skating, I think of the number of people that it took for us to get there, you know? It’s crazy when you think of the people who are supporting you and that it requires to get there. I was fortunate to have such a great support team and it’s just cool now that I’m on the other side. Once in a while, you see a kid’s dream come true and it’s awesome.”

How many players do you work with and how long are sessions?

“There aren’t really any numbers [with players]. There’s a lot; sometimes too many. It’s a shame, because I want to help everyone. But you can only be on the ice so many hours a day. What I do is very physical. I don’t want to stand around or on the side and watch. I need to participate, I need to be really physically involved, and that’s what I love so much, the fact that I can still fly around and skate, that’s my life. It’s pretty cool I still get to do what I love. Very cool, so the physical part of it is what I love so much and when I get to that point, when I physically can’t do it anymore, I don’t know, I’ll evolve into another role. That’ll be hard for me. So I try to keep myself in as good a shape as possible to do what I do.

“[Session time] differs, but generally I work with a player for 45 minutes to an hour in the offseason. During the season, especially if you’re playing games, I’ll probably schedule less time, probably 25 minutes or a half hour. I work for Tampa as well as Toronto, so I make trips to Syracuse, [the Lightning’s] farm team, and to Tampa as well. There’s the odd time I’ll go out and visit a prospect, but a large amount of my time is in Toronto.”

This is the final day of celebrating Gender Equality Month. What does it mean to you?

“When I got into hockey, there was never a thought or even a dream, I never said, I want to be a skating coach in the NHL. It really wasn’t a gender thing. When I made it, it was an expertise thing; I had an expertise that they needed. For me, it never occurred to me that there was a barrier there. I’ve never looked at barriers at all in my life. Perhaps I have to thank my parents; I have to thank my sport, because I just went after whatever I wanted to go after. I think the other thing is, I learned early on that failure is a positive thing. I didn’t have a fear of it because I failed so many times already in my skating career that I knew there’s always something to come from it. I can recall walking into this board room full of men, GMs and high-level hockey guys and I just walked in and showed them what I could do. There was no feeling that I was out of place, because I knew I had the expertise that they wanted. If you’re confident in what you do, there’s no gender barriers. Just do what you do.

“Having said that, things have changed dramatically since I’ve been in the NHL. Now when I walk into the rink, there’s a handful of women I work with every day, which is really cool. I love it because I feel that we bring something to the table. For me, it was never about a man’s world. I just walked in like I knew what I was doing. But it’s awesome now that young girls, young boys can see anything is possible. I just want kids to know, don’t think about barriers. Just do what you love and let it take you where it’s going to go. but you’ve got to love it. Be present every day and get better at what you do, and the doors will open for you.”

Photos, in order, courtesy of Barbara Underhill, Stephan Potopnyk, Skate Canada

Kurt Browning – At it again!

A tad bit more off ice training while we all wait for slipperyer places to open up again. pic.twitter.com/pdIKzTm210

— Kurt Browning (@KurtBrowning) April 21, 2020

![]()

Veronica Clarke, of Toronto, Ont., was a skating pioneer in women’s singles, pairs, dance and fours. Clarke competed from 1928 to 1938, winning 20 Canadian medals—10 of which were gold—as well as three international medals. With her pair partner Ralph McCreath, Clarke won the 1937 North American Championships, three Canadian Figure Skating Championships and along with McCreath, Constance Wilson-Samuel, and Montgomery Wilson, fours medallists in the 1938 Canadian Figure Skating Championships. Clarke is being honoured posthumously.

Veronica Clarke, of Toronto, Ont., was a skating pioneer in women’s singles, pairs, dance and fours. Clarke competed from 1928 to 1938, winning 20 Canadian medals—10 of which were gold—as well as three international medals. With her pair partner Ralph McCreath, Clarke won the 1937 North American Championships, three Canadian Figure Skating Championships and along with McCreath, Constance Wilson-Samuel, and Montgomery Wilson, fours medallists in the 1938 Canadian Figure Skating Championships. Clarke is being honoured posthumously.

Veronica Clarke’s family pleased to see her enter Skate Canada’s hall of fame

May 21, 2020)

Nearly 80 years after Veronica Clarke’s virtual retirement from competitive figure skating, her children are pleased to see she will be in Skate Canada’s hall of fame.

Clarke was posthumously named a member of the class of 2019, set to be inducted in the 2020 season, 20 years after she died. The Toronto native is considered a pioneer in singles, doubles, and fours figure skating but retired from competition in her prime when she got married and moved with her husband to New Brunswick.

“When I heard about this induction I was gobsmacked. I said ‘this is so wonderful,’” said her daughter Hilary Bruun. “We couldn’t believe it.”

Clarke started skating at the age of 10 but was in elite competitions within six years, putting together an impressive decade from 1928 to 1938. In that span she won 20 Canadian medals — 10 of which were gold — as well as three international medals.

She and pairs partner Ralph McCreath won the 1937 North American championships as well as three Canadian championships. Clarke, McCreath, Constance Wilson-Samuel, and Montgomery Wilson, won gold in the fours event at the 1938 Canadian championships.

But in 1938 she married Dr. C.H. Bonnycastle, who shortly afterwards was named the new headmaster of the prestigious Rothesay Collegiate School in Rothesay, N.B. Moving away from Ontario’s competitive figure skating scene effectively brought Clarke’s career to an end.

“I would think for someone with her experience and reputation to suddenly be cast into a different light where she couldn’t really pursue her skating, … it was probably disappointing,” said Angus Bonnycastle, Clarke’s son. “She finally gets some recognition for what she did and what she did is pretty remarkable.”

Joining Clarke in the Hall of Fame’s class in the professional category are coach Lee Barkell of Kirkland Lake, Ont., choreographer David Wilson of Toronto, and builder Audrey Williams from Vancouver.

![]()

We’d love to hear from you! Today staying in touch is easier than ever!

E-mail us your stories, photos, thoughts, suggestions and questions. We can’t guarantee we’ll print each one however we will certainly read every word and in the case of questions, find answers to them all.

Contact Celina Stipanic, Alumni and Fund Development Manager at [email protected]